Risks and Consequences.

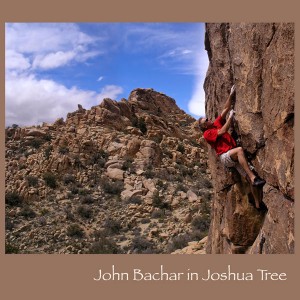

It has been a sad week in the world of climbing. The climbing community suffered a loss of a legend this past weekend. On Sunday, July 5th, John Bachar fell to his death while free soloing in Mammoth, California. If you don’t know who he is, you can click on the link to find a quick bio, but this guy was one of the greatest climbers of all time, some might argue THE greatest. This tragic event combined with my injury a couple of weeks ago in Utah brings to the forefront an issue that most climbers don’t like to think about, but should always have in the back of their mind every time they touch the rock – the concept of acceptable levels of risk. This is a concept that I journaled about last summer, and although maybe not all of it applies, it seemed appropriate to post now, considering the recent turn of events.

It has been a sad week in the world of climbing. The climbing community suffered a loss of a legend this past weekend. On Sunday, July 5th, John Bachar fell to his death while free soloing in Mammoth, California. If you don’t know who he is, you can click on the link to find a quick bio, but this guy was one of the greatest climbers of all time, some might argue THE greatest. This tragic event combined with my injury a couple of weeks ago in Utah brings to the forefront an issue that most climbers don’t like to think about, but should always have in the back of their mind every time they touch the rock – the concept of acceptable levels of risk. This is a concept that I journaled about last summer, and although maybe not all of it applies, it seemed appropriate to post now, considering the recent turn of events.

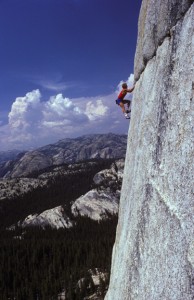

For those of you who are not aware, free soloing is where you climb without a rope, and without using any gear. Its just you and the rock. When I first got into climbing I thought that the only people who would do something like that were crazy and had a subconscious death wish. However, after becoming more involved in the community and developing friendships with climbers in my area, I was surprised to learn that several people that I knew from the climbing community (who seemed very level-headed and sane) sometimes engaged in this type of climbing. Upon hearing their reasons for why they do it (its meditative, they can get into a “flow” of movement without having to stop and worry about gear, most only do it on levels well below their physical limit, so they feel fairly safe) I realized that these people are not crazy, but actually present legitimate arguments for such an undertaking.

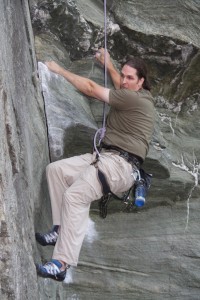

However, I still do not free solo, nor will I. This is b/c any amount of free-soloing exceeds my acceptable risk level. For the non-climbers out there that aren’t familiar with this jargon, here’s a very basic rundown on different types of climbing and the typical risks involved. A fall on a toprope with a solid anchor (usually no more than a few feet, as the anchor is always above you) is relatively benign. Not too much can go wrong here. A fall while you are leading (bringing the rope to the top of the route from the base of the cliff, clipping into protection along the way) a sport (bolted) route could get you scratched and banged up pretty badly (ahem, like my knee…), but the chances of becoming seriously injured are relatively low. On a traditional (trad) lead (placing your own gear instead of bolts), the consequences of a fall are similar to a sport route provided your gear is correctly placed in good quality rock that won’t break when force is exerted on it. If there are not many places for gear (called a run-out), or your gear/rock is bad, then the chances of injury with a fall are significantly increased. A fall on a free solo attempt will most likely result in death, or life changing injuries at the very least.

The sport of rock climbing has come a long way over the years, and with the advances in modern equipment, along with proper knowledge of that equipment’s uses and limitations, rock climbing can be a very safe endeavor. However, like any activity, it is not without risk. The job each climber has, whether it be conscious or subconsciously, is to make an assessment of what level of risk they are comfortable with. Armed with the facts and realization of consequences, he or she must determine where their acceptable risk level lies, and act accordingly.

I will use myself as an example. Toprope falls don’t bother me a bit. I won’t think twice about roping up on something ridiculously hard that I am fully expecting to flail on several times, possibly unable to even complete. The next category is sport leading, and b/c the risks are different, my attitude towards this category is more cautious. I will sport lead close to my physical limit, but unless the bolts are really close together, I am less likely to get on something that I’m not sure I can physically do, or can’t figure out possible sequences from the bottom. I look at the style of the route (overhanging but powerful lunges to big holds, vertical but with small holds and balancey moves, etc) and choose to push myself more when the climb suits my strengths. I am even more cautious when it comes to leading routes on traditional gear. I lead at a MUCH lower level than what I am physically capable of. This is my choice for two reasons. One, I feel secure in knowing that the route is at a level that I probably won’t fall at, unless something freak happens, such as a hold breaking, etc. Two, I don’t want to have to worry about placing gear when my body is in awkward, physically demanding positions, and by choosing routes well below my limit, I can usually guarantee that I will be able to place as much gear as I want in a relaxed and stress-free body position for the more difficult (crux) sections of the climb. This is where my acceptable risk level ends – anything outside of those parameters is not acceptable. I have a working knowledge in my head of what I am and am not willing to do – so whenever I’m at a crag looking at a guidebook I know right away what climbs to avoid, so I don’t put myself in a situation that I will likely deem unsafe.

I think this can be applied to the morals and values that we have in our everyday lives. There are certain beliefs and standards that I hold to strongly, so when a tempting situation comes around, I don’t have to question what my decision will be, b/c I’ve already decided beforehand what is acceptable and what is not. I am less likely to be swayed by temporary thoughts and feelings, b/c I have solid, sensible, rational logic to remind me of what I believe.

However, if I didn’t have this awareness of acceptable risk, it could easily get me in trouble, both on the rock and off. Suppose I took off on a multipitch trad route (any climbing that is more than one “pitch” means that you are more than one rope length off the ground – ie, both parties would arrive at the top of the first pitch, and then build a belay, and then the leader would take off on the second pitch, etc.). So suppose I took off on this route, and I get to the 4th pitch and realize that it is hard and scary and I don’t want to finish it. It’s not worth the risk. The only way to safely get down is to keep going all the way to the top, or to leave possibly hundreds of dollars worth of gear to safely rappel all the way down. This uncomfortable situation could have easily been avoided had I looked in the guidebook and made a conscious decision based on my realistic assessment of my ability and what level of risk I was comfortable with. As far as off the rock – take your pick of any moral dilemma you might be faced with at work, at school, with friends, family, etc. Having a working knowledge of your values and why you believe what you believe can save you from a multitude of mistakes and heartache.

John Bachar pushed himself to far greater physical and mental limits than I have ever thought about doing, so I am sure that he has been confronted with this risk assessment mentality many times throughout his life. Every time he laced up his shoes and put on his chalkbag, but did not tie into a rope, he knew what the consequences of a fall would be. Of course I can’t know for sure, but I can only assume that for him, leaving the rope in the car meant he was willing to take those risks. How someone with so many people that loved him and depended on him, (including a young son), could find those consequences acceptable is beyond me – it seems really selfish if you ask me. But he didn’t ask me, and its not my place to judge. But what I can do is search deep inside and reevaluate my own actions and choices, and make sure that I am okay with all possible outcomes of those choices, both on and off the rock, and then committ to those choices wholeheartedly. At the end of the day, I’m okay with the fall I took in Utah, even though I hurt my knee – the experiences I had on that trip were well worth the risk of the few weeks of physical setback I’m in the midst of right now. My hope is that John Bachar is at peace with the choices he made, and my prayers go out to his friends and family. 🙁

2 Responses to “Risks and Consequences.”

Good explanation of the terms- I appreciate this. 🙂

It was great to read about your travels & to see all the pictures. It brings back fond memories of Utah. I lived in SLC for 6 yrs & Provo for 3 yrs. Lehi is where they filmed “Foot Loose”. The dance took place at an old mill out there. It is not too far from American Fork where one of my sisters live. She married someone from there & has been there for over 25 yrs. She has 5 children & 3 grandchildren. In fact, one of her sons used to be a policeman in Lehi. My husband literally grew up across the street from Cottonwood Heights Rec Center. That is where I met him. I went to play sand volleyball with a group of friends & met him there where he was playing with his group of friends. We always went to the rec center to play wallyball and swim and sometimes watch hockey practices. My mother-in-law worked there for years. My mother has a life-long friend that lives up on Logan. I have been there often & snowmobiled up those mountains & visited a house built in the moutain.